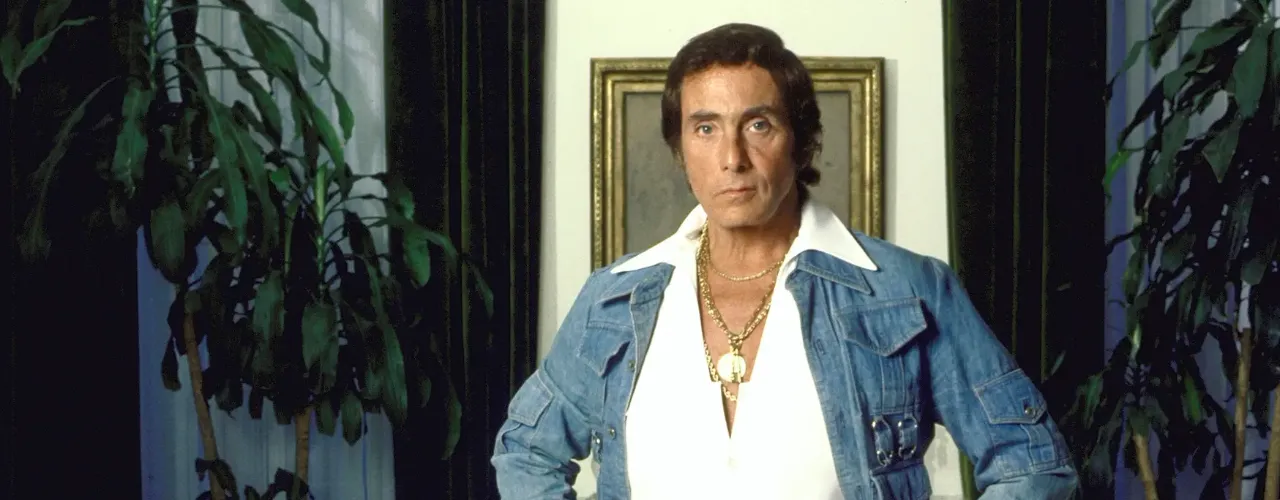

When Bob Guccione stepped off the boat from Europe in the early 1960s, he carried little more than a painter’s portfolio, a camera, and a taste for danger. He had sketched bullfighters in Madrid, sold portrait sketches on Rome’s Via Veneto, and chased la dolce vita through Soho’s smoky jazz clubs. Yet what really burned inside him was a question: Why should Hugh Hefner be the only man in the world allowed to package desire? Why should American prudery keep the most intoxicating parts of the female form in the shadows?

In 1965, on a shoestring budget in a cramped London flat, Guccione answered that question with the first issue of Penthouse. Its launch was a calculated provocation: a European‑polished rival to Playboy, infused with softer focus, deeper shadows, and—crucially—full frontal honesty. From day one, Penthouse showed what European censors had long since shrugged at, displaying honest strands of pubic hair and a come‑hither gaze that felt like a whispered confession in the night. The decision was no accident. Guccione’s market research, conducted in dimly lit pubs over endless pints, revealed that British men felt Playboy’s centerfolds were “all tease and no release.” He vowed to give them the release.

Four years later, the magazine leapt across the Atlantic, crashing onto U.S. newsstands in September 1969. It was a brazen move. America already had a king of velvet robes and pipe smoke. But Guccione was betting that beneath the thin skin of America’s sexual revolution lurked a hunger that Playboy’s girl‑next‑door fantasies could never sate. He also realized that obscenity laws were softening, and the courts were starting to side with artistic expression over puritan outrage. The moment was ripe, the market restless, and Guccione was ready to play gladiator.

The Rivalry That Lit the Fuse

Observers soon coined the clash between Hefner and Guccione the “Pubic Wars,” a cheeky pun on Rome’s Punic variety. Penthouse ignited the fight by printing images that Playboy deemed too raw for its linen‑white brand—most famously, the visible curl of a model’s pubic hair. The response was thunderous: Penthouse sold out issue after issue, and Playboy, jolted by declining ad revenue, reluctantly bared a little more fluff in 1971. From there, the photographic arms race escalated. Penthouse would edge forward, Playboy would follow, and America’s puritanical fence posts creaked under the weight of so much liberated flesh.

Guccione reveled in the chaos. Where Hefner offered golf tips and cocktail recipes, Penthouse served investigative exposés on CIA skullduggery and Vatican financial scandals—juicy stories wrapped in satin pages. He believed men wanted to feel dangerously informed as well as deliciously aroused. The strategy worked. By 1975, Penthouse’s U.S. circulation had vaulted past five million copies a month, siphoning readers from its pipe‑smoking rival and putting Guccione’s trademark cigarette holder on the cover of Fortune.

Why Candid Was King

Guccione saw nudity not as a garnish but as the main course—an art form deserving the same devotion he once reserved for oil paint. “A breast alone is decoration,” he told reporters, “but a woman wholly revealed is truth.” That credo became Penthouse’s differentiator. Hefner’s centerfolds hid the most intimate geography behind bent knees or carefully draped scarves. Guccione insisted on anatomical sincerity. He shot many layouts himself, fussing over candlelight and velvet until every pore glowed like marble in moonlight. The camera lingered on curves, folds, the hush between thighs. It was erotic but never disposable; it was voyeurism elevated to portraiture.

The culture shock was seismic. American convenience stores yanked Penthouse from shelves; church groups picketed; but the magazine’s cachet only grew. By walking the razor’s edge of legality, Penthouse positioned itself as the forbidden fruit you could actually taste—no dungeon passwords required. And with each court victory, Guccione pushed a little further, convinced that honest sensuality was a civil right.

Enter the Penthouse Pet

To embody his vision, Guccione introduced the Penthouse Pet—a monthly muse selected not only for photogenic beauty but for a certain slow‑burn charisma. Unlike Playboy’s Playmates, who floated through the magazine like wholesome daydreams, Penthouse Pets stared back at the reader as if they’d been caught mid‑tryst. They were real, accessible, scandalously alive.

For aspiring models, the Pet title became a golden ticket. A single pictorial could propel an unknown waitress from Des Moines onto the talk‑show circuit, land her movie cameos, or secure lucrative photo contracts in Europe and Japan. Penthouse paid generously and syndicated its imagery worldwide. Some Pets parlayed the acclaim into mainstream acting gigs; others launched entrepreneurial empires in fashion, cosmetics, or adult entertainment. Exposure, quite literally, translated to exposure.

That allure wasn’t just about fame or cash. Many models spoke of creative liberation—of owning their sexuality on glossy paper rather than letting Hollywood’s casting couches dictate their narrative. U.S. laws of the era left women’s bodies heavily policed; to strip for Penthouse was to plant a defiant flag on your own skin. Paula Jones, controversial though her circumstances were, famously said she posed because she “deserved control of [her] story” and needed to pay mounting legal fees.

Calculated Risk, Magnetic Reward

Was posing the right career move? For many, yes. Penthouse Pets of the Year often commanded six‑figure endorsement deals and worldwide publicity tours. Even the cautionary tales—like Vanessa Williams losing her Miss America crown—proved the brand’s potency: Penthouse could topple institutions and forge celebrities overnight.

Yet it was never a guaranteed fairy tale. Some models faced backlash from conservative hometowns or casting agents who still drew red lines around explicit nudity. But in Guccione’s orbit, they found a patron who saw them as subjects, not props. He paid for acting classes, invested in their photography portfolios, and championed them as entrepreneurs. No other men’s magazine spent so lavishly nurturing its female stars.

The Vision Behind the Velvet

So what truly drove Guccione? Beyond profit, beyond one‑upmanship, lay a radical thesis: That erotic freedom and intellectual dissent were twin edges of the same blade. He wanted Penthouse readers aroused and awake—ready to challenge authority in the bedroom and the boardroom. His magazine’s mix of sex and scandal was no accident; it was an editorial manifesto.

Guccione also hungered to fund his own artistic obsessions. The magazine’s cash paid for an Old Masters art collection, financed the infamous epic film Caligula, and bankrolled an Atlantic City mega‑casino that nearly sank his empire. Each project sprang from the same bravado that birthed Penthouse: Why not try what others fear?

A Legacy Written in Satin Ink

Today, digital pixels have replaced glossy staples, yet the Penthouse origin story remains a case study in entrepreneurial audacity. Guccione saw a chasm between what men craved and what gatekeepers allowed, then filled it with 84 pages of parchment‑thick rebellion. The decision to print pubic hair wasn’t smut for smut’s sake; it was a statement that adult sexuality deserved an adult presentation.

Penthouse was created because one man believed desire should be depicted honestly, that investigative journalism could live beside satin‑draped thighs, and that a woman fully seen is a woman fully respected. And while Playboy may have built the mansion, it was Penthouse that lit the chandeliers.

As long as models dream of being Pets—of that dazzling centerfold coronation—and as long as readers still hunger for stories that make the pulse race, Bob Guccione’s original dare will echo: Show them everything. Every secret. Every curve. Every truth.

Author: Lea Parkins